Life sciences, pharmaceutics and the interpreter

If they say “life sciences interpreting,” then you know you’ve hit the real “meat.” As a child, I heard the phrase “the remedy can be worse than the cure.” It’s a perfect fit for interpreting in the field of life sciences, where one slip of the tongue can be very costly.

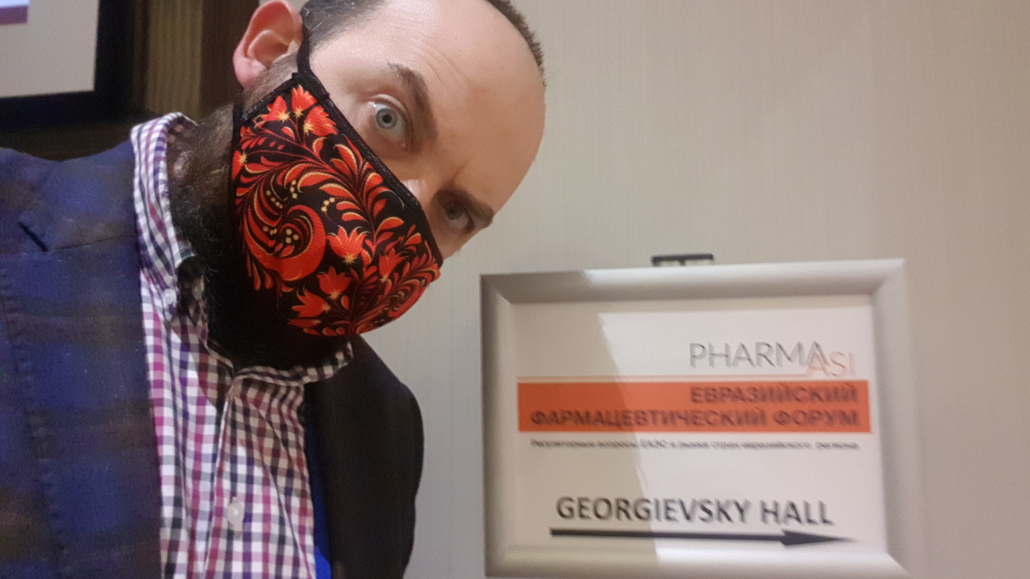

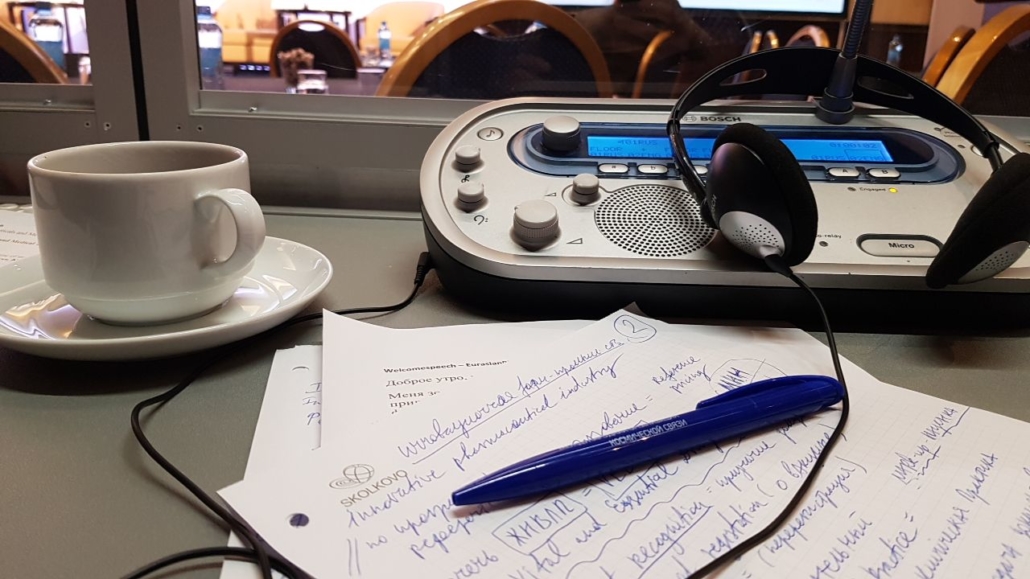

It all starts with preparation. You can’t just sit down in the booth and start simultaneously interpreting for a conventional pharmacists’ forum, a round table on introducing pharmaceuticals onto the EAEU or EU markets, or a panel discussion on labeling issues. Experience is everything.

I would compare simultaneous interpreting in the field of pharmaceuticals and medicine to alchemy. After all, isn’t pharmaceutics just the distant descendant of alchemy? Active ingredients, space-age devices, super-accurate scales, punches, vivariums, and all that? The mystical side of human activity, associated with many rumors and myths. Who wasn’t struck by that in 2020?!

A disease is spreading across the world: a communications gap between the pharmaceuticals industry, PR agencies and the finished information product, in other words what people will eventually hear. To bridge this gap, it’s important to correctly interpret what is being said behind the scenes.

What’s the first phase in the emergence of an interpreter who specializes in life sciences? We’ll use the alchemy term nigredo, meaning the decomposition stage, to refer to this phase, a long and multifaceted one. It’s all about practice. Future conference interpreters are in training, gaining lateral knowledge. They interpret during the installation of pharmaceutical equipment and at factories, they work next to machines and scales, admire packaging machines, rustle blister packs… The number of specialists working at this level is relatively high.

They can usually tell stories like these: “I was on a project where they were running a clean room – I had to put on a beard cover”, “I interpreted next to a working psychiatric hospital, where you could hear all these terrifying screams all the time”, “we flew to Italy for a GMP inspection, we ate strawberries and parmesan in the evenings, but we never saw the sun because we spent the whole time with the inspectors in warehouses and checking rodent control facilities.”

The pinnacle of the first stage of pharmaceutical interpreting is simple repetition. For example, the names of the substances and materials themselves: these can be rattled off in a list by professionals, without batting an eyelid, but soon become a muddle when someone without the required training attempts to tackle them. Try this: say the following in your head “bevacizumab, metformin, antibiotic resistance.” Now try and say it out loud. Human vocal cords are often not intended to pronounce such constructions. It’s something you have to learn.

The second phase of becoming an interpreter is refining your skills. This is equivalent to the albedo or regeneration stage of alchemy. At some point you realize that you are drawn to this medical “meat”, this pain and decay. It’s yours. That’s when the additional study begins, and you pay closer attention to the topic itself. Attention is a priceless resource. If you start to devote more of it to life sciences, then you close yourself off from, say, working on oil and gas jobs or the projects of some company or other. But behind one door (GMP inspections, for example), numerous others are ready to open (in growth media, pharmacopoeia, international research projects). This is where it gets trickier: interpreters are specializing, they create their own glossaries, they know the correct wording and turns of phrase. Incidentally, what is required of the interpreter is the correct wording and the ability to articulate and understand what the speaker is saying. In short, more skills are required.

You might be translating complex descriptions of the systems used to calculate analyte concentrations, materials, data flows, etc. After some time, you find yourself surrounded by piles of folders, files and standard operating procedures. You need to be familiar with calculation and control systems, and safety regulations. Beside you is a huge machine analyzing HIV tests and in the next room is a row of chromatographs. You’ll spend several long hours interpreting questions about them.

Sometimes you’ll be at a factory, looking at an ancient Soviet tablet press. It is manually operated, so the pharmacist can control the density of the tablet pressing – a conventional oblong.

Time passes. You learn on each project, chalking up weeks’ worth of interpreting hours. You find yourself in the thick of configuring filtration systems, you learn about the problems of manufacturing and storing hazardous substances, you meet many experts from Europe, the USA and India and you delve further and further into the processes. You’re an interpreter, gaining a deeper and deeper understanding of the topic, and this gives you the right to claim the status of an interpreter in the field of “pharmaceuticals.” This ensures communication. And the value proposition of such interpreting grows, since the cost of each subsequent translation includes what came before. Multilayered knowledge emerges.

The third phase is the narrowest. Rubedo is the final act. Clearly, it is not every day that the titans of manufacturing get together for defining, industry-wide events, exhibitions and conferences. But this is where professional simultaneous interpreters, who have 7–10 years’ experience in pharma, come in. Because “the remedy can be worse than the cure.”

If you don’t know that somewhere in a pharmaceutical company’s warehouse are kept jars of soy agar, you won’t know how to interpret on the topic of growth media. Experts in the culinary arts might interpret about soy broth, but they’re at WorldSkills, dealing with culinary topics.

If you haven’t acquired a practical knowledge of the technological requirements for the tumbler mixers that apply coatings to tablets, you won’t be able to translate the current European or American standards for adding a film coating to tablets.

A pharmaceutical interpreter looks differently at the mysterious FDA markings on jars of vitamins. He or she may remember that conference where the speaker compared the requirements and procedures of the American FDA for the testing of particular substances. Or, for example, the EAEU regulations that apply to a medical product with FDA registration.

Words have meaning. And the higher the level of the discussion, the greater the meaning of the words. There is a higher cost attached to the words and the decisions that will be made on the basis of these words are more important. It is always a one-off. It’s generally said that professional medical interpreting sounds different – special.

That is why some of my colleagues are on good terms with some of the speakers, having got to know each other in the margins of events. That is why the interpreting world is a small one. And as I said above, it all starts with preparation.

Maxim Sirenko, April 2021, life sciences interpreter since 2008,

works with Janus Worldwide